Click on the links below to discover how the centre of Croydon earned its nickname ‘Little Manhattan’ and read further about the history of the area’s iconic buildings.

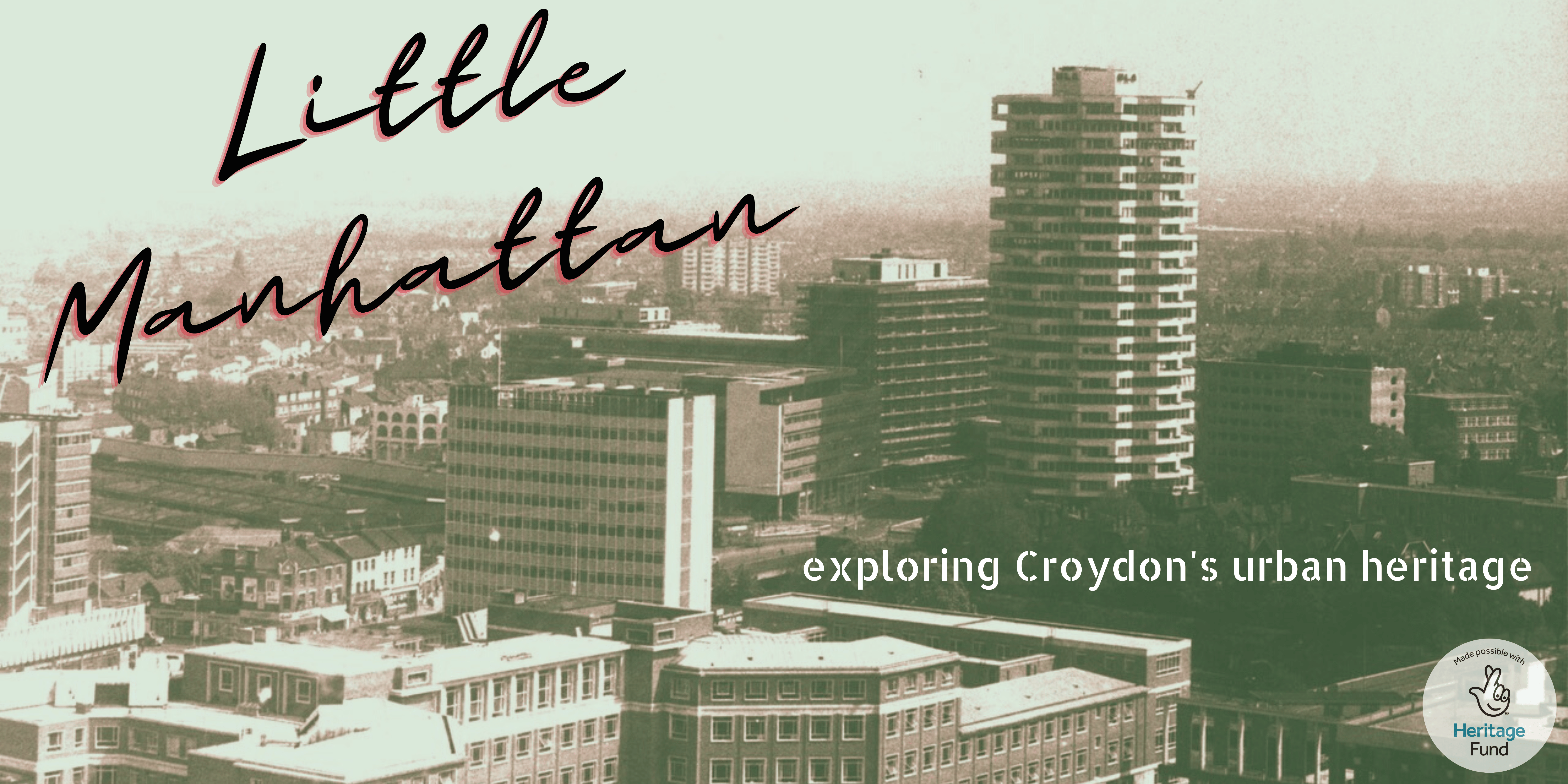

In the post-war period between the 1950s and the 1970s, a regenerative building boom transformed Croydon’s urban landscape from being a town made up of traditional brick buildings to an architecturally modern urban space, rivalling the design, skyline and environment of major cities, earning it the nickname ‘Little Manhattan’.

This development was led by Alderman James Marshall, often called ‘The architect of Croydon’, who had been apprenticed to the Croydon architect, Sir Henry Berney before the First World War. Marshall was elected as a conservative councillor in 1928, going on to join several influential committees such as Electricity and Lighting, Finance and the Food Control Committee during World War Two before becoming an Alderman in 1937.

Plans to develop the town centre had started in the 1930s when Southern Railway sold their Fairfield Site to the Council and a competition to design a new Civic Centre was launched. Architects were appointed in 1937 but plans were postponed when war came soon after. In 1943, a reconstruction committee was appointed with the main focus to provide housing to replace bombed-out properties and by 1955, additional housing had been completed for 20,000 people.

During the interwar years, council departments outgrew the Town Hall accommodation and many took over large Victorian properties along Park Lane and Wellesley Road. Pitlake Technical College burnt down during the war and with plans to rebuild on the site of the Public Halls where the School of Art was also housed, part of the Fairfield Site was earmarked for this new development.

Architects Robert Atkinson and Partners had been appointed to the scheme by the Council in 1937, and when the first plans of Croydon College were made public in 1951, they were condemned in the Croydon Advertiser as being too traditional, ‘adorned with sham columns and colonnades and other frills borrowed from the time of the horse and cart’. Robert Atkinson died in 1952 and his partner Anderson took over.

The final plans were for a smaller building, although it was still the largest Technical College in the south of England when it opened. Despite the change of plans, much of Atkinson’s design was retained, using Portland Stone, brick and copper roofs. Building started in 1953 with the first students admitted in 1955 and a formal opening by Queen Elizabeth II in 1960. The negative reaction to the college’s traditional architectural style probably led to experimentation with modern designs and alternative materials such as concrete and glass.

The NLA Tower (or Number 1 Croydon) was created by Richard Seifert, one of the most famous commercial architects of the 1960s, acclaimed for his wide range of office development schemes and the unusual forms he gave his buildings. The best-known of his other developments is Centre Point in London’s West End.

At 270 feet and 24 storeys high, the NLA Tower was the tallest building in Croydon for many years. It was built between 1968 and 1970 and has been given a range of nicknames over the years – ‘the wedding cake block’, the threepenny bit building, or the 50p building (if you were in Croydon after decimalisation in 1971). Its full name was Noble Lowndes Associates Tower, the building’s original principal tenant. After refurbishment in 2000, it was renamed Number 1 Croydon.

The building has become a key landmark for pedestrians, bus passengers and train arrivals at nearby East Croydon Station. A system of subways were constructed to enable pedestrians to access the station, the Post Office and number 10 Addiscombe Road, the only original building left undemolished due to a dispute with its leasehold tenant.

Miss Kathleen Harding, a solicitor and the tenant of East Bridge House, 10 Addiscombe Road, hampered construction of the NLA Tower for several years. Out of respect for her late father, and with legal skills at her command, she resisted all offers from the developers to sell them the property, and it was feared that the entire construction project would have to be abandoned. Instead, plans for the NLA tower block had to be altered to accommodate her, with a new roundabout carefully carved out around her home. Miss Harding’s house remained standing in the shadow of the tower until it was finally demolished in 1973.

Corinthian House, on the corner of Lansdowne Road and Sydenham Road, was designed by Richard Seifert and partners, the architect responsible for London’s famous Centre Point building and the NLA Tower, now known as No 1 Croydon.

This 11-storey block was built in 1965 with Henry Grovenors as the partner in charge of its design and construction. It’s a sculptural building, typical of Seifert’s 1960s work, dramatically formed, constructed in concrete and faced with bands of mosaic tiles.

The most dramatic aspect of the design is the spectacular concrete cantilevered entrance canopy, springing out horizontally from beneath the first-floor level. This feature, accompanied by the v-shaped concrete structural columns beneath the building, known as ‘piloti’, are examples of Seifert’s attempts to emulate the famous French architect Le Corbusier, with tall structures sitting raised above the ground. These details created an iconic building that shows the significance of this period of architecture.

In the 1960s, Croydon High School for Girls also sold its site and moved to a new building outside the town centre. It was replaced by Apollo and Lunar House which were speculative developments by Harry Hyams, the reclusive property tycoon. Their names reflect the era’s NASA Apollo programme of missions to the Moon, and Hyams liked to give his high-rise buildings space-age names, such as Astronaut, Space, Orbit, Planet and Telstar House.

Apollo and Lunar are twin towers built between 1967 and 1970 by Denis Crump and Partners on either side of Sydenham Road. They are 20 storeys high, facing Wellesley Road, each with a hexagonal satellite extending out, mirror images of each other.

Lunar House is considerably larger than Apollo House. Its extra rear slab has a distinctive skeletal superstructure in precast concrete on its roof, which can be spotted from miles around.

After completion, the blocks stood empty for over a year before being occupied by government departments, notably the Home Office Immigration and Nationality Directorate (now known as UK Visas and Immigration) in Lunar House.

The iconic Whitgift Centre, known as one of the forerunners of the modern shopping experience, was built on the site of the Trinity School of John Whitgift, which had occupied 11 acres between the new office centre and North End since 1931. The original site of the school provided an oasis of playing fields in the centre of the town, surrounded by shops from its entrance in North End. However, in 1965, the school moved to its new location in Shirley, leasing the very sought-after land to developers, who demolished the nineteenth-century school building to construct the Whitgift Centre, which at the time was an eight-and-a-half million-pound office and shop development.

The architects took advantage of the sloping site to build a two-level shopping precinct which could be entered naturally from North End and at the upper level from Wellesley Road. The two levels were connected by goods and passenger lifts and two large circular ramps, which are no longer in place. One feature that many people remember was The Forum pub in the middle of the centre, accessed from the ground floor by a moving walkway or ‘travelator’. Polygonal in shape, it proved a welcome focus for many shoppers and local workers at lunchtime.

The first shop to open was Boots on 17 October 1968, and the centre itself was officially opened in October 1970 by Her Royal Highness the Duchess of Kent. It was the largest covered shopping centre in London until Westfield opened in White City forty years later.

Plans to upgrade the existing shopping areas, including redevelopment by Westfield and a new John Lewis store, haven’t materialised in recent years, but discussions to revitalise the shopping centre are still on track to encourage more footfall to the town centre.

By October 1945, the Council launched its development plans for the next 50 years. As well as the Civic Centre, plans now included a greatly widened Wellesley Road and Park Lane with an underpass underneath George Street, a flyover across High Street and Old Town to Duppas Hill, a new bus station, car parks and many new office buildings funded by private development.

Although this was modified, it led firstly to a Town Planning Scheme, then to the Croydon Development Plan of 1951. In 1954, the Government ended building restrictions, setting off an office building boom in the South East, encouraging the movement of businesses and workers out of central London. To avoid more delay, a private Bill was promoted in parliament and became the Croydon Corporation Act of 1956. Initial progress on redevelopment was slow due to the continuing shortage of men, materials and money.

Building materials and styles had changed since the war as the shortage of steel and emergence of concrete as an alternative led architects to look at new ways of construction. Slabs could be poured onsite and a lot of facing panels were made of precast concrete in out-of-town factories and transported easily by road or rail and assembled on site. Brutalist features such as visible construction materials and unusual formations of window arrangement and external decoration became the signs of a new phase of Croydon’s development.

Initial work started on the eastern side of Wellesley Road and Park Lane on the site of the former Public Halls and the eastern part of George Street. Building lines were pushed back to widen the roads and office developments included Norfolk House in 1959 followed by Suffolk House and Essex House. This area became known as Little East Anglia.

Norfolk House, designed by Howell and Brooks, was the first tall building to be built in Croydon, with an 11-storey block and lower 7, 4 and 2 storeys running around this central core from Wellesley Road to George Street. It comprised a wide range of shops at street level. Key features are angled windows in chevron pattern at the first-floor level and light brick cladding.

Suffolk House was built in association with Essex House by Raglan Squire and partners in 1960 to 1961 as part of the first generation of office buildings. Suffolk House is 4 storeys, with black marble sill-bands and curtain walling. It has splayed corners which were a planning requirement and were condemned by the Croydon Advertiser as “destroying the rectangular shape of the building”. Essex House, was an 11-storey slab, tapered at both ends, standing on a podium with an inner courtyard. Initially, it was notable for the green colour of its curtain walling; but this gradually faded and the building was empty by 1991 and demolished in 1998. A recent 44-floor housing development, Ten Degrees, now stands on this site and is currently Croydon’s tallest building.

After the building of Norfolk House in 1959, the focus turned towards the development of shops and offices between Park Lane and High Street. The area was previously occupied by the Greyhound Hotel, a former coaching inn fronting onto the High Street, but with its yard and outbuildings extending back to Park Lane. The complete development of the 6-acre site was undertaken by Charles Ellis and financed by the Church Commissioners.

This development included Katharine House, Ellis House, Park House, Pearl Assurance House, St George’s House, The Greyhound Hotel and St George’s Walk and took three years to build between 1962 and 1965. It was meant to be the showpiece of the new Croydon, architecturally as well as economically.

St George’s House is often credited to Borough Engineer Allan Holt’s desire for a really tall, landmark building in Croydon. Asked what he meant by “really tall”, he is said to have responded, rather glibly “twice the height of Norfolk House”. The resulting building, 23 storeys to Norfolk House’s 11 storeys, was the result. It stands 260 feet high and was the tallest building in Croydon until 1970. The building dominated the town centre and at its opening, The Mayor of Croydon remarked that Nestlé, who occupied the building, could be excused for believing that they owned Croydon.

It was built in concrete with vertical lines of white capstone and brick infilling to very high standards including, for example, cavity floors to take computer cables. A new building at the foot of the tower block was added to relocate the Greyhound Hotel and is still remembered with affection by music lovers, playing host to the likes of David Bowie, Queen and Deep Purple. Staff at the Fairfield Halls remember the battle of the bands, between themselves and the Greyhound on a Sunday night, when they would try to catch the highlights at both venues. It never regained its pre-move status and after various changes in image, became the Blue Orchid nightclub in 1989 before closing in 2004.

St George’s Walk, the shopping precinct below, was slow at attracting tenants, and units were small. This meant that those who did set up businesses there were often small independent and specialist shops. It suffered from the outset from a wind-tunnel effect and was soon superseded by the nearby Whitgift Centre. Attempts to improve the surroundings included roofing over part of the mall and also installing advertising boards at angles to limit the wind-tunnel effect.

Those who lived in Croydon during the sixties and seventies may remember the Pasta San Georgio restaurant, the Panino and Sergio’s sandwich bars as well as a model shop, Jewellers, and hairdressers like Swankers and Shears.

Other shops, restaurants and cafes in St George’s Walk that evoke fond memories for some Croydonians include ‘A wool and sewing shop that used a grabber to reach the wool; the Madhouse clothes store that blasted out music; a camping shop; suits from Ralph Taylors; and lunch from the bakers shop where you could buy a huge cheese baguette and a strawberry tart with a 15p luncheon voucher.’

Several plans for redevelopment have been considered, including Park Place, a new shopping area across Park Street and into George Street in 2005, and Queens Square by the Chinese R&F Properties Group in 2018. A large proportion of the site has now been completely demolished, bringing to an end a piece of Croydon’s history that lasted just over fifty years.

The Fairfield Halls building is named after the plot of land it’s built on, which is where Croydon’s historic fairs were held for centuries. The fairs traditionally held there were brought to an end in the 1860s when work began to build Croydon Central Station, whose platforms were on the site of what is now Queen’s Gardens and the Town Hall. The station closed in 1890 because it was unprofitable, and after it was demolished a short section from the main line as far as Park Lane remained in use as Fairfield Yard. This engineer’s yard operated until the 1930s when it was bought by Croydon Council, who promoted a competition in 1935 to design a new Civic Centre for the future. Plans were delayed by the outbreak of war and resurrected in the mid-1950s.

After the completion of the Technical College in 1959, the priority for the redevelopment programme was entertainment and cultural facilities. The old Public Halls on the corner of George Street and Wellesley Road had been demolished in 1957, while on the High Street, the Davis Theatre and the Grand Theatre had both closed in 1959 and been replaced by Davis House and Grosvenor House office blocks.

To fulfil the need for a new cultural venue, Fairfield Halls was built between 1960 and 1962 by Robert Atkinson and Partners. Using a very different style to their building of the Technical College, a large central concert hall with the auditorium at first-floor level was built between the smaller Ashcroft Theatre and the Arnhem Gallery. The building’s appearance is very similar to a scaled-down version of London’s Royal Festival Hall, built a decade earlier. Hope Bagenal was the acoustic consultant on both projects, and Fairfield Hall’s acoustics benefited greatly from what had been learnt on the Royal Festival Hall’s earlier build. Consequently, Fairfield Halls’ world-class 1,802-seat Concert Hall is famed for its acoustics, which are regarded as amongst the best in the UK, resulting in many classical recordings and rehearsals taking place in Croydon.

Fairfield Halls was opened by Her Majesty the Queen Mother in November 1962. The inaugural performance in the concert hall was given by the BBC Symphony Orchestra led by Sir Malcolm Sergeant with soloist Yehudi Menuhin. In the Ashcroft Theatre, Peggy Ashcroft delivered a monologue written especially by John Betjemin, followed by the play, Royal Gambit with Michael Denison and Dulcie Gray.

The following year, on the 25th of April 1963, the concert hall hosted two performances by a new band called the Beatles, as part of a Mersey Beat Tour just a month after their first album, Please Please Me was released. A young man, Andy Wright, who was doing work experience at the halls, had a camera with him and captured some unique early images of the group on stage which were rediscovered nearly 50 years later.

Control for the Fairfield Halls passed from the Council to a charitable trust in 1993. In 2016, the building closed for major refurbishment and re-opened in September 2019 managed by BH Live, a social interest company based in Bournemouth. Many of the building’s 1960s features have been refurbished and remain to showcase the history of the building.